What makes The Colossus look so gigantic?

_____

GIANT, noun: (in folklore) a being with human form but superhuman size, strength, etc.

Dictionary.com

There are very tall people among us now, and no doubt there always have been. Here are photos of just a few of them:

Zhan Shi Chai (1840s-1893), Chinese,

Eddie Carmel (1936-1972), Israeli-American,

Ralph Madsen (1897-1948), American, and

Sultan Kosen (1982-still living), Turkish.

These unfortunate people have often ended up being exhibited as freaks in circuses, and as there are few other job openings for them or anyplace where they "fit in," they usually grudgingly accept their fate and allow themselves to be exhibited. Their abnormal size is usually a result of a tumor on their pituitary gland (which regulates growth). Rather than being super-healthy, their condition often causes them to die young. These people are startlingly tall compared to the rest of us, but of course none of them have been "giants" of the kind that we know about from legends and fairy tales. They are not the type to cause an earthquake when they walk or eat a pile of whole roast oxen for dinner.

The giants of mythology and stories and movies and so on are always huge beyond a size that humans have ever grown to, and are extremely strong and powerful and often looking for a fight with gods, or with other giants, or else they're looking for a meal. No matter if they might be supposedly "friendly," such a giant would be frightening, as even the most careful and courteous giant might inadvertently step or sit down on people or animals or houses, etc., or knock over a building. He (sometimes she) would also use up the resources of the local "little people" in a hurry.

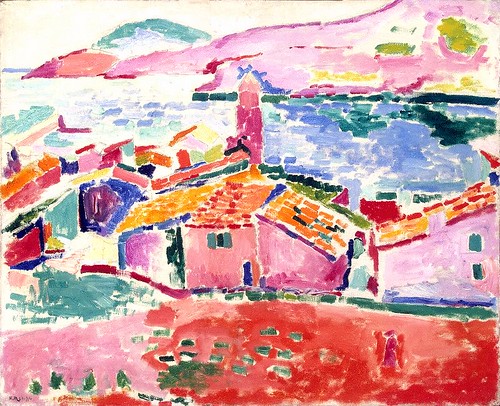

Though it's obvious that giants of this type have never actually existed in real life, they've been invented by writers, artists, and storytellers as metaphors to fill different needs. For instance, it is likely that the giant ("Colossus") in the painting shown below is meant to represent the Spanish people resisting

Napoleon's invasion.

The Colossus - 1808-10

A clearer reproduction

Artist:

The Colossus - 1808-10

A clearer reproduction

Artist: This painting was formerly attributed to

Francisco de Goya, but some experts now believe it is by

Asensio Julia (1760-1832) (

Here is a much better article on Julia, but in Spanish), a pupil and friend of Goya (Spanish - 1746-1828)

Picture, from Wikimedia, is in the public domain

To me this giant looks definitely of gargantuan size and strength, in addition to appearing somber, serious, and powerful. One would think mountains would crumble as he walked by.

What are some of the things the artist has done that make this giant seem so gargantuan and powerful? It's not just the size he has made the figures in the foreground, which are tiny in relation to the giant. If we are able to see this picture more clearly and in a larger size, we'll see there are people and animals in the foreground fleeing the area, but I didn't even notice them when I first looked at this dark reproduction of the picture, and wasn't aware of them until I read about them later; they just looked like specks of debris to me. When I saw

another reproduction, I could see them, but even when I didn't know they were there the giant looked extremely gigantic. In fact, it seems to me that you could remove the bottom third or so of the picture, leaving out all the comparatively tiny humans and animals, and he would still look of monstrous size.

And what if we leave the bottom of the picture intact - Why is it that we don't see the Colossus as a man of normal size and the fleeing people and animals as being very tiny?

There are several things I can think of that the artist has done to make the Colossus look so gigantic and powerful. Here is what I've been able to come up with so far:

Borrowing the immensity of the sky

- There is the fact that he blends in with the black sky, making him "as big as the sky," since in many places you can't really see where he ends and the sky begins. I think that is one of the most effective methods the artist has used to imply monstrous size. What is bigger than the sky?

Making the giant appear to be rooted in the earth

- Although he seems to be part of the sky - or the sky seems to be part of him, at the same time he seems to be "rooted" in the earth (his body from the thighs down is either in a very deep valley or at the bottom of the ocean...neither one of which seems likely...or he is supposed to be buried from feet to thighs in the earth, not immobilized, but in order to appear figuratively

deeply of this place and not about to be unsettled by mere interlopers), and this secure attachment to the ground gives him a look of great stability, adding to the impression of power and invulnerability.

Comparing his height with the height of the clouds

- He rises above the clouds...that alone makes him seem huge.

Contrasting his size with that of the clouds

- There is also, of course, the contrast in

size between the clouds and the giant.

Contrasting his size with that of figures in the foreground.

- Mentioned above.

Having his eyes closed to show control of a huge reservoir of emotional energy

- The giant appears to have closed eyes. To me at least the closed eyes add to the feeling of power and strength contained within his massive and stable body. The closed eyes remind me of closed vents on a steaming pressure cooker. They show that he's holding back extremely strong emotions in order to keep them under control, presumably in order to make the best use of them, though he could explode with fury and action at any second.

Making him appear reddish

Making him appear reddish

- One thing that helps make him look powerful is the lighting, which presumably is caused by a setting sun, making him reddish, and therefore hot looking, which causes him to appear very "alive" and possibly angry or otherwise possessed by a powerful emotion about to erupt.

Illuminating the giant from a low angle

- The light shining on the giant is coming from a low angle, illuminating him as a just-setting sun would throw dramatic reddish light on a monstrous thundercloud to the east. Lighting him from "below" helps make him seem even taller.

Positioning his body so that he looks even bigger

- His raised arm and fist make him look bigger -- It gives him more bulk; and although his back is in blackness, much of its outline is clearly defined by the lighted clouds beyond it, so that we are aware of the thickness of the middle of his body -- If the background behind his back had also been black, he would not have looked so big and powerful. He would have look very tall, but "flimsy," not thick and strong.

Positioning him so that he appears to be rising

- Also, the raised arm, capped by a huge fist aimed upwards, along with the nearby head of the giant (which so strongly pulls our attention so near the top of the picture), makes it seem as if he's rising (and, as Arnheim [see Note 3, below] points out, what is rising is what we are alarmed by -- what is drooping or lying flat does not scream out "danger" to us; it calms us down as it is non-threatening). A rising giant (and/or the rising arm and fist of a giant) is definitely alarming.

Using a strong diagonal to show action

- The raised arm is the only really noticeable diagonal in the composition. We all know that a diagonal that is not supporting something signals "action," though that action could be "rising" or it could be "falling." The arm does look like it's rising, rather than falling, as the fist seems to "pull it up." Action, especially "rising" action, implies energy and power.

Providing a viewpoint that makes the giant look huge

Providing a viewpoint that makes the giant look huge

- Another thing that adds to the impression of hugeness is how the giant appears from our viewpoint. Even though he is a great distance away, we are looking "up" at the giant from approximately the level of his thighs, knowing that the rest of his lower body is far below our eye level. Just imagine how it would affect us if we saw such a thing from this viewpoint in real life.

Putting him in the upper part of the picture

- There is also the fact that objects that are higher up in a picture seem heavier than they would if they were lower in the picture. The giant is the only thing in the upper part of the picture, other than the clouds (which are "floating"). His raised arm and fist plus the thickness and three-quarter view of his body give him great width in this part of the picture. If his arm had been at his side and the hugeness of his back not defined by the light-colored clouds behind it, he would have looked tall but not massive. But he

does have a raised arm and fist and etc. Not only that, but as mentioned, just because these things are so high up in the picture it makes him seem even heavier, and stronger. (If a person can easily hold up that much weight - the weight of his monstrous body - we can assume he is very strong).

Putting him in the distance

-- Oddly enough, something else that makes him look huge is putting him at such a distance from the foreground. How do we know that the giant is far in the distance? One way we can tell is that the mountains are in front of him (i.e., between the giant and the viewer) -- We may not assume that those dark shapes are mountains but even then we know that the entire foreground,

whatever it is, is between him and us, cutting him off at the upper thighs, thereby, to our eyes, pushing him back behind something, which of course indicates that he is in the distance.

-- Another thing that implies distance is the dramatic difference in lighting between the foreground and background. Where the giant is, in the distance, the evening sunlight is still trickling through, but in the foreground you can hardly see what is going on; it is as if it's already nighttime there. Such a difference in lighting indicates a difference in depth. Knowing he's at a great distance, the fact that he

still looks enormous is rather stunning.

Putting him in the vertical center

Putting him in the vertical center

- He is basically, as far as the legs and main trunk of his body is concerned, in the vertical center of the picture (though turned toward the left). Being in this position stabilizes him and makes him seem invulnerable.

Having him turn toward the left

- The fact that he is turning toward the left might show an attempt to push back at something that is coming at him from that direction. Action in a picture generally is imagined to begin at the left side and in this case the giant stops it and keeps it from going further. (Due to the fact that his base is firmly "planted" along the central vertical of the picture, the giant does not seem to have come from elsewhere, but to be defending himself from his home base, there in the center of the picture.) Having him turned toward the intrusion shows that he is quite aware of the danger and is able and prepared to do something about it ("the sleeping giant" has been awakened and he is furious).

Including fleeing people and animals

- Although these are hard to make out (at least in the copies of the painting I've seen), when you do notice them, they appear to be moving at top speed away from the giant, indicating, I would guess, one of three things:1) The giant is scaring them; 2) They know that something horrific is about to happen involving that giant and whatever he is facing; or 3) They are trying to escape whatever the giant is confronting, leaving him to take care of the problem. In any of these cases the giant, be he friend or foe, is having a terrific impact on these people and their animals.

Selecting a suitable format

- The picture is in the shape of a vertical rectangle, though not far from being a square. That is, it's "squat." This format reinforces the stocky, sturdy, powerful look of the giant.

_____

Although I have not seen the original painting, and I have probably not even seen a good reproduction (the picture shown here is the only one I've studied; I chose it because it was explicity said to be in the public domain), the ways in which it appears to me that this picture makes the giant look tremendously huge and powerful are still valid. My point is to reveal ways in which to make something look immense and fightfully strong and energetic. Certainly techniques such as these have been, and are, used not only in stories and drawings, paintings, photographs, etc., but also in other art "products"...from architecture to advertising...to make something - anything - appear to have similar qualities.

_____

NOTES:

1) The thoughts presented above on how the artist has made the giant appear to be so huge and powerful are my own, based on what I have read and understand; I am not pretending to be an expert, but I am very interested in composition and study the subject constantly.

2) I'm aware that

The Colossus is now considered by some (most importantly, the Museo del Prado) to be the work of Goya's apprentice, Asensio Julia, yet it is very much in the spirit of what Goya himself would have done and some experts still believe it was painted by him. It doesn't matter here (in this post) who the artist was, as we're talking about how the composition makes the giant look gigantic, but it's interesting.

Here are some articles on this subject that you might want to read:

Wikipedia article on The Colossus (El Coloso), in English

Wikipedia article on El Coloso (The Colossus), in Spanish - This one is much longer and more interesting than the one in English.

"Does it matter who painted The Colossus - Goya or his apprentice?", Article in The Guardian (U.K.),

January 27, 2009, by Adrian Searle

Museo Nacional del Prado on the attribution of El Coloso

This is in Spanish, though Google will translate it. It's a long, very detailed, illustrated explanation of why they consider that

El Coloso was not painted by Goya.

3)

Rudolf Arnheim

Books by Arnheim consulted for this post:

---

The Power of the Center

---

Visual Thinking

---

Art and Visual Perception

To subscribe to the Thinking About Art Monthly Newsletter, see toward the bottom of the page.