Lessons from Edvard Munch's The Murderer in the Lane.

The outside edges of a painting play a major role in determining what your picture is about.

We can't just start painting without considering how the edges affect the subject we are trying to portray. What is inside the picture must be related to the outside perimeter of whatever we're painting or drawing on from the very beginning ... as well as to the center of the picture (but of course we only know where that center is when we know where the edges are).

Usually, when we are not just practicing we paint (or draw, etc.) in order to present a subject in such a way that other viewers might see it as we do and respond to it as we wish them to.

I think that all artists have these object in mind, though some who may be earnestly trying to get their message across may not realize how they are sabotaging their own efforts by ignoring the edges of their pictures, not taking them into account at all except as places where they must stop painting because they've run out of room.

Before we even choose the size and shape of the surface upon which we'll be painting, we must have in mind exactly what we're trying to say with our picture. What is it that has impressed us with regard to the subject that we want to impress upon others? Once we have that in mind, we can think about how we will accomplish this.

There are many things to think about when composing a picture, but one of the most important and probably the first to be considered is where the main subject will be placed and how large or small it will be, etc. in relation to the center and to the edges of the picture (as well as to everything else that's going to be in the picture). If you just paint whatever is "out there" that you are looking at (or what you're thinking about) until you get to the edges of your canvas, the intent of the picture will probably be unclear, to say the least. In fact my personal opinion is that it's not "art" unless you have planned for it (whether consciously or intuitively) to say what you want it to say.

If you have nothing to say, except perhaps that the subject of your painting is beautiful or interesting (though you can't think of exactly why and otherwise it has no particular meaning to you), you might as well just take snapshots or make sketches. You can always use the photos or studies later, after you've thought about what you want to say about this subject.

Why must we worry about the edges? Why can't we just put our main subject in the middle of the picture and paint outward from there until we reach the edges of the canvas? Because, as Rudolf Arnheim points out in his book The Power of the Center, "the nature of an object can be defined only in relation to the context in which it is considered." That context includes the surface you're painting or drawing on, right out to its outer limits.

"[T]he character, function, and weight of each object changes with the particular context in which we see it," writes Arnheim. Further, he says: "A frame of a particular size and shape defines the location of the things within its space and determines the distances between them." He is not talking here about the kind of frame you put a picture in and attach to a wall, but about the outside edges of the picture, or the "boundaries" of the picture, and how everything in the painting relates to those edges.

I'll give an example. If your subject was a very distressed murderer leaving the scene of the crime in great haste, would you put him in the middle of the picture? Perhaps. It depends on what else you do in the picture (with colors, values, rhythm, shapes, etc.) and what else you want to say about him. But take a look at the picture painted in 1919 by Edvard Munch (1863-1944), called The Murderer on the Lane.

Here you can see how large the painting is, as this page shows a recent photo of the original painting in a gallery with people looking at it -- Scroll down to the bottom picture on the page to see it.

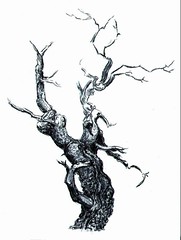

In the painting we see just the head of someone hurrying down a dirt lane lined with frightening-looking trees, away from a dead body. His or her simple, almost cartoon-like face shows concentration and anxiety.

Assuming the head you see (a man's? a woman's?) at the bottom of the picture is that of the murderer (not a horrified passerby), you may wonder why (let's call this person "he") isn't somewhere near the middle of the picture rather than just barely seen at the bottom edge - After all, isn't the murderer the subject? I don't think Munch would put a murderer in the most "stable" part of the picture (the center), or anywhere near it. Whatever is in the center would look like it's not going anywhere soon, if at all; it would be as if planted there with no intention of movng away. The killer is crazy -- quite unstable -- and he's leaving the murder scene (and leaving it rather empty, except for that dead body), hurtling himself toward me (the viewer), in fact, and so near the bottom edge (with most of him out of sight) that his advance toward me seems unstoppable; he is "falling" right out of the picture, pulled by gravity, so to speak...as we associate the pull of gravity with the bottom of a picture (and the effect is even stronger if a significant amount of ground shows, as it does here).

In fact, if the murderer was in the center and also much larger in relation to the size of the painting, he might look like he was paralyzed, hardly able to move, the more so the bigger he was in relation to the outside of the picture. If his head filled the whole canvas so that it reached the edges it might look as if he were going to explode...but that is not the same as looking as if he were intent on getting the heck out of that place (and in fact there would be no space left in the picture in which the scene he was leaving could be depicted).

If he were situated very near or even touching the top edge of the picture rather than at the bottom he would probably not seem threatening to us at all. That edge would "hold him" up and away from us (like a helium balloon stuck to the ceiling), especially if it were toward the right side of the picture (the left side is where action usually begins, and it unfolds -- or appears that it will unfold -- toward the right, suggesting that whatever is happening will be completed by the time it reaches the far right side...unless it seems to be crashing down toward the foreground, perhaps, as in this painting).

Of course there are other things you can do with a picture to indicate the state of mind of someone, or the trajectory of his path, the likely escape route, or etc., but these are some of the ways in which the edges work ... you can modify or cancel the effects with other things you do, but let us see how the edges can work for us; it is useful to know these things if only to make sure we are not inadvertently saying something we don't want to say by where we're placing things in a picture.

In this painting the artist has made the murderer's head small in relation to the whole picture, and left plenty of room behind him so that we can see what he is fleeing from, and he has placed his head right at the bottom edge, almost out of the picture.

One reason that having the subject at the bottom edge of the picture is very effective is because, as mentioned, he seems to be uncontrollably leaving the scene. It's also effective because it's such an odd place to find the subject that it makes it very conspicuous...especially since it's only a head, with no body in sight. It's scary, and riveting.

The very dominant, large thick tree just to the left of the center of the picture is in a place and of a size such that it balances (visual weight-wise) the murderer's head that's just to the right of (and below) the center. (And the tree also looks something like a person, with a face on the thick branch at the right -- a witness to the murder, watching the murderer as he rushes away -- maybe it even represents the murderer in the act, with its branches upraised like arms perhaps wielding the knife.) There are other tree witnesses further up the lane. These trees not only play roles in the drama as witnesses, but they are lifting themselves and their branches up to the very top edge of the picture (and beyond), balancing the murderer who is running out of the picture at the bottom edge, so that the picture is not bottom-heavy, and so we look upward to the rest of the picture as there is so much in it that we need to see besides the murderer's head.

The picture shows the lane behind the murderer, where the dastardly deed was done (with the dead body still there to prove it), and although we see that the lane is not on a hill, there is still a "hill-like" effect that we feel since it starts at the horizon and comes toward the foreground (and continues beyond it out of the picture in our minds) ... Although we realize this is flat land being portrayed, we can't help but get a feeling that things are starting "high" (because the end of the path is up high in the picture) and coming "down" (to the bottom of the canvas) toward us. Also, we have a view of the murderer from slightly above his head, looking down on him, which increases the feeling that he is going downhill. What is in the foreground near the bottom edges of the picture is strongly affected by gravity in our "unconscious" minds if not in reality. An artist like Munch knows these things if only intuitively. And so the lane delivers (dumps?) the murderer into our laps.

The relatively calm (but not silent) area at the left side of the picture balances all the action on the right.

Note that the horizon (where all looks peaceful and humdrum) as well as the four edges of the picture (and the vertical trees - and there's even a square in the sky that appears to be the moon...what else could it be) are based on the Cartesian grid - These horizontal and vertical lines -- as I say, including those of the outside edges of the picture -- stabilize the picture and serve as contrast with and intensifiers of all that is bizarre and unnerving in the painting; they also determine for us what is up and what is down...We must know this in order to "feel" the gravitational pull at the bottom [this is something that we perceive below the level of consciousness] that is ridding the scene of the murderer.

All of the eerie, nervous lines and the sickening colors and so on in the picture that cause anxiety in us are more effective because of this contrast, i.e. chaos and anxiety contrasted with seeming permanence and stability of vertical and (especially) calm, non-threatening horizontal lines.

I have hardly begun to touch on the ways considering the edges (and center) of the picture can make our pictures more effective, but it's a beginning, and certainly enough for one post.

_____

NOTES:

1) The Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts is a book by Rudolf Arnheim published by the University of California Press.

2) The Murderer in the Lane is also called The Murderer on the Lane and Murderer in the Avenue.

LINK:

The Artchive - Commentary on and Pictures by Edvard Munch. There is very interesting commentary here on Munch.

0 comments:

Post a Comment