Some people may wonder why I'm writing so much about how we respond to "flat" landscapes (or cityscapes, or most any view other than of a single compact object) when it may seem to them to have little to do with art, but of course it does have much to do with art.

An artist has to know (if only unconsciously) what effects horizontality/verticality/mixed heights have on a viewer. As is the case with any other aspect of a composition he or she must know what to include or not include, and what to emphasize and what to deemphasize in order allow the basic shapes to help get across what it is he or she wishes to "say" about a subject and not inadvertently give the "wrong" message or make it confusing.

Just for a few examples of what you might be trying to get across: possibly you want to emphasize the subjugation of nature by man for his own ends, showing a landscape that seems to not allow for anything accidental, unplanned, or different from what man "needs" - or to make life "easy" - no matter that it might flourish in that environment ... Nothing that is not "necessary" is allowed to protrude/impose itself and although horizontality itself may not be required to achieve the effect you're after in this case (or in others), it could be something you would make use of.

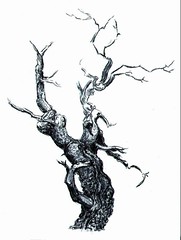

Or you might want to show the triumph of nature (not necessarily plant life ... this could include other manifestations of individuality and accidental effects that interfere with the intention of man to impose his will on what comes naturally) over man's efforts to manipulate it and hold it back/down, in which case you might show a variety of directions and heights, not emphasizing the horizontal at all, or else show definite horizontality peppered by contrasting, very vigorous verticals of various heights (think "weeds"). Or you might want to show a happy mixture of the two ideas - man and nature getting along just fine.

Or perhaps you'd want to give the impression of "hopelessness" via a barren-looking very flat landscape or show "individual uniqueness and spontaneity is respected and accommodated here" via a landscape in which there is a variety of plant life: bushes, trees, vines, seemingly growing naturally, appearing to not have been planted intentionally by people, where it appears that people have arranged their lives around what's in nature rather than the other way around...As I say, it need not be "plants" and could even consist entirely of man-made structures that appear to not have been constructed to fit a strict plan but instead to have arisen "spontaneously." Or a combination of plants and structures. It could include whatever is seen in the air, too.

These are only a very few examples of the endless possibilities.

You can see how horizontality can help you achieve what you want in some cases, or hinder it if you're not careful in others. (If you do not think about what impression your picture will make because of such things then it may confuse people or you may inadvertently be sabotaging your intention.)

The bottom line is that what is out there (in "real life" or on canvas or paper), no matter whether it's recognizable as things we see in the everyday world or not, has one or more (usually more) "messages" for us, and in art we must know what these are (otherwise why would we bother to produce art ... We can try to copy what we see as if we're a camera or we can just dab or scribble away and try for something "pretty" or "interesting" but if there is nothing in particular we want to communicate, why do it? And what is "artful" about it?).

The messages our pictures convey are not usually communicated only by the alleged "subject matter." They are communicated by the way the entire picture is composed -- through lines, colors, textures, shapes, patterns, rhythm, size relationships, directions, etc. We "understand" what the "whole picture" means because of how all of these things work together. We understand not only because of what we have learned from reading and listening, and from looking at pictures, and from watching videos and movies, from thinking about these things, and even from personal experiences with whatever the subject matter might be, but also from our what you might call "generic" or "non-specific to any particular subject" familiarity with the physical world we live in (i.e., the earth and the tiny part of the universe we're able to experience from here) and how it basically "works." (Our understanding of how gravity works is an example, and this is very important ... There are several posts on this blog that have to do with gravity, though there are presently only two that have gravity as a keyword that I've noted on the list at the right side of the page -- You can take a look at that list for gravity - Click on the word and posts that have quite a bit in them about gravity will come up on one page ... but, also, any post that has to do with the Cartesian grid is also about gravity as the Cartesian grid exists because of gravity.)

Click on the words "horizontal format" in this same list at the right side of each page to see the posts that are most closely related to this one you are reading now.

Artist: Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875)

Picture Source: Wikimedia

What do you think Corot might have been trying to communicate about man and nature in this picture, and how did he make use of horizontality to help him do so?

_____

JUST REMEMBER THAT A FLAT LINE SUGGESTS THAT "THERE'S NO LIFE HERE ... THERE'S NO THREAT ... IN FACT IT'S PRETTY DEAD HERE ... WE CAN TAKE OVER NOW."